The school year has just begun here in Australia. It’s a time of great anticipation, resolution and excitement – I love the sense of possibility that accompanies this time. For many of us – having had a break – it is also a time of adjustment. In a sense, we return to our ‘teacher selves’ and with that, is an opportunity to think about that identity: how DO we see ourselves as teachers and how does this impact on the way we teach? I remember hearing Ken Robinson (in a lesser known talk) once describe teachers as gardeners. This is always a metaphor that has appealed to me. I like the nurturing connotation, the link to nature, the need to tend and care, the combination of planned and unexpected and, of course, the symbol of growth.

Read MoreSomething to talk about: Dialogic teaching – putting classroom talk at the centre of inquiry

I am delighted to share this guest post from a long time colleague of mine - Julie Hamston. Julie and I have written a number of books and articles together over the years and I continue to learn a great deal from our conversations about inquiry, teaching and learning. Julie's expertise is in the area of language - and, as you will see from this post, she is particularly fascinated in the role of talk in the inquiry classroom. I have previously posted some thoughts on the language we use with students and am in no doubt that one of the most important things we can do for learners is to strengthen our understanding of and skill in managing dialogue to support their' thinking. Talk is our central and perhaps most powerful 'tool of trade', as Peter Johnson reminds us: "Teachers' conversations with children help children build the bridges from action to consequence that develop their sense of agency" (Choice Words, 2004:30) I know you will find Julie's post thought provoking - I hope it gives you something to talk (and wonder!) about at your next team or staff meeting. Effective teachers of inquiry operate with a finely tuned set of strategies to encourage students to make their thinking visible and to share their understandings with others.

Although these strategies have sharpened our attention on the relationship between language and thinking, I suggest they are limited unless we better understand the way that classroom talk is intimately connected with student learning. Deep and meaningful inquiry is dependent upon the linguistic leverage teachers provide to students through language that is modelled, generated, recycled, consolidated and stretched within the context of inquiry. The explicit pedagogic language of the teacher, consciously focused on deepening and expanding the linguistic content of student responses, combined with strategies for exploratory and collaborative talk, helps students develop the discourse practices (such as predicting, reasoning, explaining, justifying, interpreting, problem solving) fundamental to inquiry.

This view is not a new one. Classroom-based researchers from all over the world have demonstrated through close analysis of teacher-student talk and student-student talk that the quality of linguistic interaction and feedback in the classroom impacts on the quality of learning. That said, I strongly believe that more time and patience needs to be devoted to authentic dialogic interaction in inquiry classrooms and that teachers make a stronger investment in the language both they and the students produce.

This dialogic approach to teaching involves two integrated foci on language:

- the language-specific routines that teachers draw upon within any inquiry focus: questioning; prompting; eliciting and cuing student responses; ‘pressing’ for more clearly articulated detail, information or explanation; repeating, reformulating and elaborating on student responses; and recapping what has been learnt.

- the collective, purposeful, and reciprocal language exchanged between students and between students and the teacher.

When we think of inquiry-based learning and the emphasis placed on shared work, problem solving, making connections and thinking through complex issues, the importance of dialogic teaching is clear. Neil Mercer and others view talk as helping students do the hard work of learning. Dialogic inquiry involves students in seriously working with the ideas of others, considering and challenging evidence, worldviews and perspectives, and reaching logical conclusions.

My recent work on dialogic teaching

Throughout 2014, I have been working with the Principal and staff of Meadows Primary School in Victoria, Australia to establish a whole school commitment to dialogic teaching, initially around inquiry-based learning. The student demographics at this school are shaped by generational poverty; household and neighbourhood disadvantage due to chronic unemployment and a high proportion of sole parents; significant ethnic diversity in the community, including Indigenous Australians and new and settled migrants for whom majority English is an additional language; as well as widespread first language ‘impoverishment.’

We were interested in the quality of teacher and student talk in the classroom. We wanted to see, more clearly, the ways in which teachers used language to scaffold thinking and learning, to build, deepen and extend their students’ language repertoire so they could make their reasoning ‘visible.’ I designed a program that combined professional learning on dialogic approaches in the classroom, analysis of classroom transcripts and videos, classroom observations, feedback and evaluation.

Teachers were also required to collect data of their own talk interactions with students and to analyse these in terms of the language techniques they were using (for example, did they reformulate students’ responses? Did they put a ‘press’ on students’ language? Did they cue students into possible answers?). In addition, they were encouraged to introduce exploratory talk techniques to their students (the Thinking Together project coordinated by Mercer and colleagues at the University of Cambridge formed the basis of this task https://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk).

Teacher volunteers were then invited to be involved in a pilot project involving the trial of dialogic approaches within the context of inquiry-based units of work. Two year levels responded: the Foundation Year (consisting of four teachers, led my me) and Years 3 and 4 (consisting of four teachers and facilitated by the school’s lead teacher, Adam).

From: Tayla Cosaitis’ Year 3/4 class: Ground Rules for Talk.

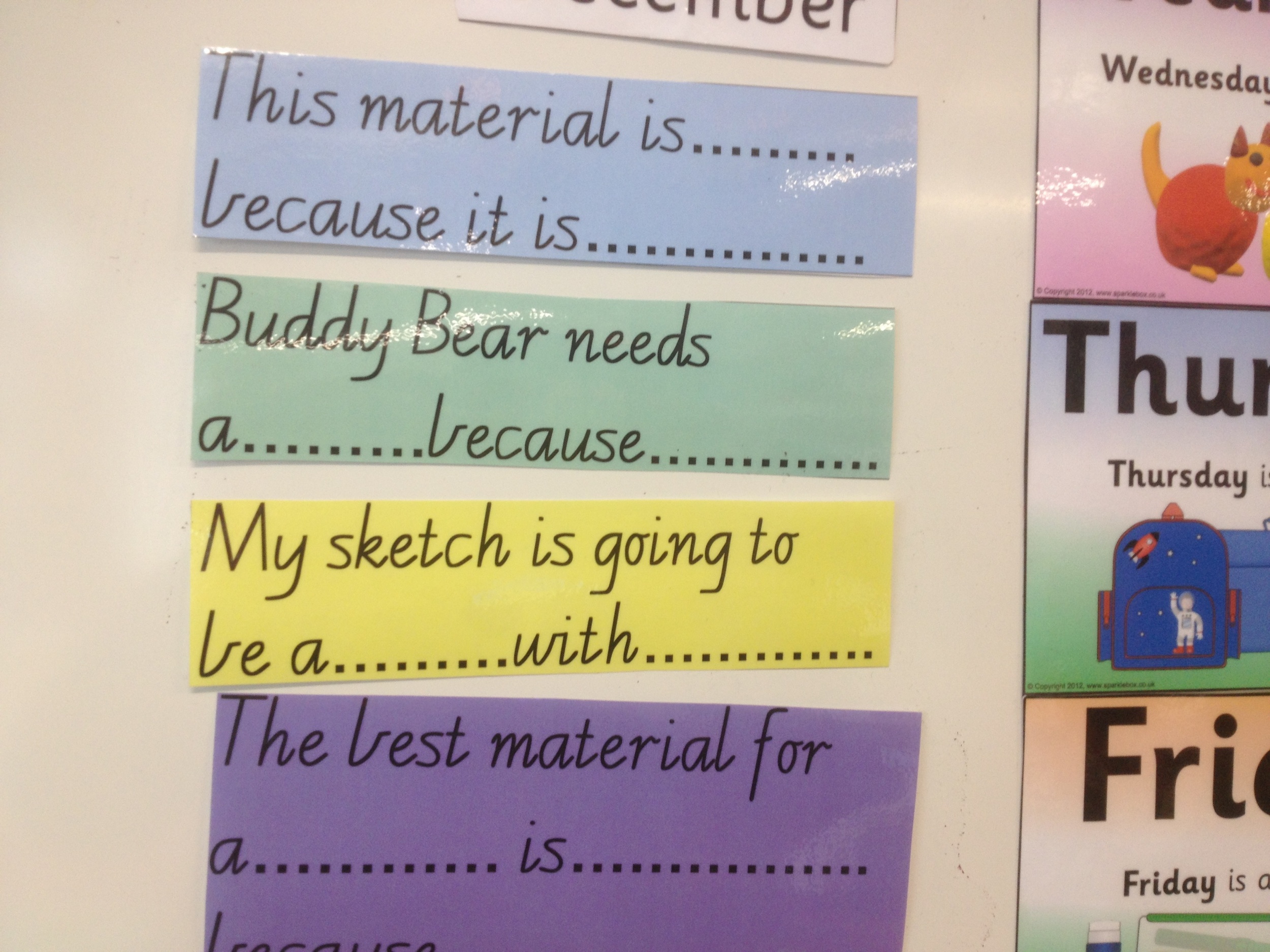

The Foundation teachers, working with 5 year olds (Sarah Lynch; Laura Di Lizia; Stephanie Webster and Libby Morris) collaborated closely with me on building students’ capacity to share their thinking, using longer stretches of language incorporating reasoning words such as ‘because’ and ‘if.’ In consultation with the research literature, we designed language frames relevant to their students’ inquiries (“ I like your idea because…” ; “ I will build a …. because….”; “I will use… because….”).

From: Laura Di Lizia’s Foundation class: Design, Creativity and Technology Unit – Building a House for Buddy Bear.

The teachers also ‘planned in’ their own and student language to their inquiry units, established ‘talk buddies’ for an initial foray into exploratory talk, and introduced students to the ground rules for active listening, talking and sharing with others.

The analysis of transcripts was central to the teachers’ professional learning. Examples such as this one were used to identify (i) the language repertoires used by each teacher and (ii) any growth in the students’ linguistic reasoning:

Teacher: Sofia, can you tell me what you have used to make your couch? (Eliciting a response)

Sofia: I have used material. We used cotton balls and we got the Buddy Bears to test them out on them… and we used cardboard and we used bubble wrap.

Teacher: Great. You used lots of things. Can you tell me why? (Request for student to provide a reason). So can you say “I used cardboard and bubble wrap and material because… (Providing a language frame as support).

Sofia: Bubble wrap.

Teacher: Put it in a full sentence. “I used …” (Putting a ‘press’ on the student’s language in the hope for a more comprehensive and reasoned response).

Sofia: We used materials because to make it comfy (sic). We used cotton balls to make it even more comfortable. We used cardboard to make it strong. We used bubble wrap to make it soft. We used glue to glue it together (Putting language and thinking together).

The explicit apprenticeship of students into the discourse practices of inquiry has been so positive that teachers report a shift in students’ capacity to use talk to provide evidence and justification, and to think through alternatives. Importantly, the teachers say they are more focused on their own language use. Great examples of this from the teachers in Foundation year include:

- Reformulation of student responses (Did you mean…?)

- Direct elicitations – (“Can somebody …? Who knows…?: “I want to know what you know about sketching.”)

- Exhortations (“Who is thinking the same/different?”)

- Repeating student responses to consolidate learning (“Well that’s a lot of information there. I’m going to break it down for everyone. Shreya said …. Shreya went on….. and explained more………………….)

- Recaps to consolidate understanding (“OK, so we have used our observation frames to look at the weather…”)

- Connecting feedback to inquiry (“Great thinking!; “I love the connection you just made.”)

- Building on student responses (“I just want to bring it back to what Louie was saying.”)

- Requests for reasoning (“You have to tell me why. Remember to make a prediction and tell me your reason.”)

- Putting a ‘press’ on student language (“Can you put your answer in a full sentence?”; “Can you begin by saying ‘I think…”; “Remember our language frames: “I predict…because…”)

Work continues on dialogic teaching at Meadows Primary School in 2015 and 2016 – watch this space?

Contact

Dr Julie Hamston is an education consultant and a Senior Fellow in the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Australia. She can be contacted by email at: j.hamston@unimelb.edu.au

If you are interested…

Alexander, R. Dialogic teaching. Retrieved from http://www.robinalexander.org.uk/dialogic-teaching/

Dawes, L. (2008). (Chapter 2 ‘Talking Points’) The Essential Speaking and Listening: Talk for learning at Key Stage 2. Retrieved from https://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk/resources/About_Talking_Points.pdf

Hamston, J. (2006). Bakhtin’s theory of dialogue: a construct for pedagogy, methodology and analysis. The Australian Educational Researcher, 33, 1, 55-74.

Haneda, M. W., G. (2010). Learning science through dialogic inquiry: Is it beneficial for English-as- additional-language students? International Journal of Educational Research, 49, 10-21.

Haneda, M. W., G. (2008). Learning an additional language through dialogic inquiry. Language and Education, 22, 2, 114-136.

Mercer, N. (2008). Talk and the Development of Reasoning and Understanding. Human Development, 51, 90-100.

Mercer, N. D., L. (2010). Making the most of talk: Dialogue in the classroom. EnglishDramaMedia, 19-25.

Taggart, G., Ridley, K., Rudd, P. & Benefield, P. (2005). Thinking Skills in the Early Years: A literature review. Retrieved from http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/73999/1/Thinking_skills_in_early_years.pdf

Zhang, J. D. S., K.A. Collaborative reasoning: Language-rich discussions for English learners. The Reading Teacher, 65, 4, 257-260.

Inquiry and the "specialist" teacher.

I have been thoroughly neglectful of this blog! It is somewhat ironic that I spend a good deal of time talking about the need for reflection; time to think and slow down instruction for deeper understanding – while I rush around allowing myself precious little time out to write! There is a back-log of posts I am eager to get out there so I hope that the remainder of the year will see them come to fruition. A number of issues have got me wondering of late. Perhaps the most intriguing has been about the relationship between what we describe as ‘specialist’ programs (in elementary/primary schools) and inquiry. The expertise of specialist teachers in any primary school is often a hugely undervalued resource. It is not uncommon for me to run a workshop where specialist teachers don’t attend due to the perception it is ‘not really relevant ‘ to their subject area. And yet – some of the best inquiry teaching I have seen occurs in art rooms, music studios, gymnasiums, etc.

I have taken my ‘wonderings’ to friends who are professional artists, musicians, writers, etc. and, without exception, they describe their own learning and the development of their skills as a true process of inquiry. Sure, they have all benefited from others showing them how to execute a skill and from the wisdom of masters in the field – but they also talk passionately about the need to explore, experiment, meander, question, reflect – the hallmarks of inquiry learning. I sometimes wonder whether my beliefs about my skills in visual arts (I am an ‘I can’t draw’ person) might have been different had I not been expected to 'do art' the way the art teachers insisted - had I not been compelled to create a given ’product’ the same as everyone else's and had I been given the opportunity to see what I could discover for myself with some freedom to explore.

Of most interest to me are views about language teaching as not compatible with inquiry – yet I know of no more inquiring an experience for me than the quest to master new language in a non-English speaking country! What we need in these situations is a desire to master the skill, the learning skills to help ourselves do so and the availability of an expert/coach when we need one!

My work in international schools in particular increasingly involves teachers who work in single subjects areas such as music, PE, visual arts, languages, and so on. I am noticing some recurring questions in our conversations - some specialist teachers are frustrated by the restrictions that exist due to timetables or other people's perception of their role. Common questions include:

- How can I use an inquiry approach when I have such short sessions with the children? (some specialist teachers have as little as 30 minutes per lesson)

- How can we use inquiry when we have no time for collaborative planning with generalist classroom teachers?

- How can we help classroom teachers (and students) see our role more deeply than giving them time release or ‘supplementing’ their unit with shallow, related, activities?

- Ours is a skill-based subject – how can we use inquiry when we have to actually ‘teach’ kids what to do?

- We are expected to make links to the ‘units’ that classroom teachers are doing but they often don’t suit our program – how can we manage this challenge?

For those now anticipating a clear, decisive response to each of those questions – be prepared to be disappointed! The very reason these questions emerge time and time again is that they reflect some pervasive misconceptions that still exist in relation to inquiry OR they are the product of the way we have organized our schools/programs. Having said that, there are several things I have found helpful to consider when thinking about the relationship between inquiry and specialist programs. Here are my thoughts – I would love to hear yours!

It’s an approach – not a classroom ‘subject’. We can ALL be inquiry teachers. While we continue to associate inquiry only with ‘units’ of work in the classroom – these issues will persist. When we see inquiry as an approach rather than a subject, then it becomes relevant to all teachers, all learners. Even in a 30 minute session, teachers can ask themselves “how can I provide more inquiry based learning experiences for my students? How can I encourage them to explore, make their own connections, ask questions, etc.” A simple example would be a PE teacher choosing to give her/his young students time to experiment with different ways to get a ball from point A to B as quickly as possible before providing any direct instruction on techniques. The lesson is flipped from ‘watch me, listen to me, then have a go…’ to have a go – then we will see what we discover AND what we need to focus on. And while we are on the subject of PE, check out these great examples of specialists as inquiry teachers: http://www.pyppewithandy.com/ and http://www.iphys-ed.com/inquiry-in-pe

Working on the same ‘content’ does not make it any more inquiry based. In the past, our attempts to make stronger connections between specialist and generalist programs have often manifested in specialist taking on the same ‘topic’ being worked on in the classroom. I don't need to go into the problems associated with shallow, tenuous links. Suffice to say, forced connections that can compromise the integrity of the discipline do nothing for student learning. Let’s not confuse the term ‘integrated’ learning with ‘inquiry’ learning. That said, where learning can be genuinely integrated through shared skills and concepts the result can be powerful. If the content offers a perfect ‘context’ for student learning in a specialist area then go for it – but never force the issue!

Transdisciplinary skills are just that – transdisciplinary. Regardless of the program/curriculum, most inquiry schools recognise some framework of skills and dispositions that are shared across all subject areas. These may include, for example, social and self management skills thinking skills and communication skills. As I have discussed before, these skills should be inquired into as part of students’ learning experiences. Highlighting the same skills in specialist programs (not all of them every time – but at least some!) helps students transfer their learning AND widens the scope of inquiry. For example – students exploring ways to give others feedback in the classroom can consciously practice and extend that skill in PE, in art, etc. If any aspect of planning is shared between generalist and specialist teachers I think it should be this.

Create opportunities for shared teaching. Watching each other at work is a very effective form of professional learning. In an inquiry school, opportunities to observe practice helps build bridges between specialist and generalist teachers AND within specialist programs. Observations across subject areas helps us think less about the content and more about the pedagogy. I am not a PE teacher – but have learned a great deal from watching skilled, inquiry based PE teachers work with students. Watching the way an inquiry based art specialist promotes reflective and critical thinking can help transform the teaching techniques for literacy in the generalist classroom.

Identify shared learning strategies and build a common language for students to ‘talk about learning. We all know that opportunities to transfer and practice skills and strategies in different contexts are vital for deeper learning. When specialist and generalist teachers communicate with each other about the strategies (such a visible thinking routines) they are introducing or revising at any year level – students have a greater chance of experiencing this transfer.

Consider flexible timetabling, shared use of learning spaces, more personalized access to specialist ‘studios’: Perhaps one of the biggest impediments to more authentic, inquiry based approaches to ‘specialist’ programs is the structures used in most schools – eg: a lesson per week for each class at a set time. As this time is so often used for generalist collaborative planning, it can mean there are precious few opportunities for shared, cross program conversations –it may also serve to reinforce some students’ perception of inquiry as a ‘subject’ that happens in their classroom rather than elsewhere. Several schools continue to explore ways to re-think the way they structure for specialized learning in these areas. Arrangements include flexible timetables, for example - library teachers might be booked on a needs basis and work alongside the classroom teacher to coach students’ research skills. Art rooms in some schools have become studios where students can access materials and expertise of the specialist teacher beyond their designated session time. If schools offer an ‘itime’ or ‘genius hour’ program – specialist teachers and any designated learning spaces can be utilized if the timetable allows.

It is so exciting to see the growth of understanding of inquiry as an approach to teaching and learning rather than something that happens in ‘units’ that are occasionally integrated into specialist programs. We have come a long way.

I would love to hear from more of you about how you have approached this in your schools – what’s the relationship between ‘inquiry’ and specialist subject areas in your school?

…Just wondering….

Making a real difference through inquiry

Late last year, I was fortunate to spend some time with Hilary Green - then a graduate teacher in a local school here in inner Melbourne. Hilary described in enthusiastic detail, an inquiry she and her team had facilitated with their 6 &7 year old students. The inquiry started out as an investigation into the culture of play but culminated in the students experiencing the power of giving to make a difference to the lives of others. Along the way they built skills as researchers, designers, film makers, collaborators, communicators and activists! I asked Hilary to write about this experience as a guest on my blog – here is a great example of a rigorous yet emergent approach to inquiry – and real action as a result! I am sure you will enjoy reading her reflection.

About the inquiry.

" Our inquiry was initially into ‘The Culture of Play’ (part of a whole school project into culture). The Year 1 teaching team thought that by exploring play, a subject the children in which the children were experts, we would be able to uncover the complexities of culture. The first semester saw us explore many questions we had about play. What do we play? Where do we play? How do we play and even why do we play? From there, the children narrowed down their ideas to categories their ideas into three things that affect play that they want to explore. At the end of term we presented our research in the form of a film festival, a nighttime celebration involving all children and parents where the children presented short films they had made.

The film night was made up of 3 short films, each using a different “language” of expression. This included animation, silhouette mime and a puppet theatre. Each of the films was based on an experience we had exposed the children to which included visits to retirement villages another school and the Melbourne Museum.

The seeds of action...Prior to the film festival, one of the children suggested that we raise money from the night and make toys for asylum seeker children in detention because they didn’t have toys. After some discussion, the group agreed and a new branch of the inquiry grew. Like real designers, the children began by making some prototyopes and co constructed some success criteria - they wanted the toys to be:

- Safe

- Able to be shared with friends

- Long lasting

- Comforting

- Imaginative

- Used in many different ways

- Made with strong materials

- Age appropriate

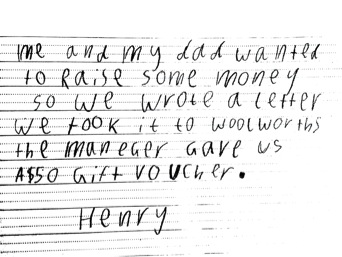

Children were so excited about this action they naturally involved their families after hours:

Some parents shared their knowledge of the design process and another whose work involved defending the legal rights of refugees, was able to answer the children’s increasing questions:

Some parents shared their knowledge of the design process and another whose work involved defending the legal rights of refugees, was able to answer the children’s increasing questions:

- My dad goes to court and argues about refugees coming to Australia. He argues with the government to make sure that refugees are safe. He came to talk to us about refugees. Hannah

- David showed us on a world map where refugees are coming from. Alima

- Refugees are people who are forced to leave their home because it is too dangerous. Holly

- Detention centres are places where people cannot come and go as they like. Vittoria

The children worked in small groups to develop initial designs and prototypes of toys for the children in detention centres. They then reviewed each others’ designs each other feedback.

Another father, who designs soft toys came in to share the toys he designs and makes. The children thought of the questions to ask him:

- How do you put the stuffing in?

- How do I create the different colours on my material?

- How do you know what materials to use?

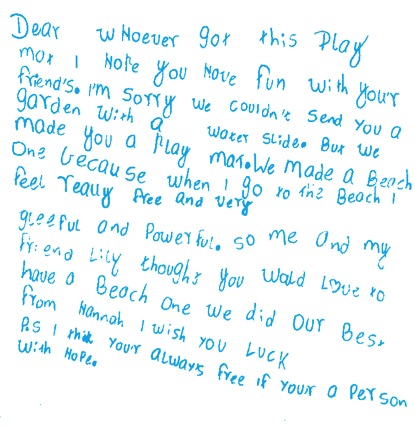

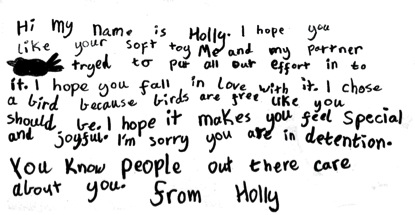

At all stages of the process, the children were inquirers – whether they were investigating how to create their own film, asking experts questions, testing out designs, learning how to physically construct aspects of their toy/game – they had to question, investigate and meaning make in authentic ways. By the end of the inquiry, the children had collaborated to produce some beautiful toys and games to give to the children being housed in detention centres in Melbourne. They decided to write letters to accompany their gifts – the letters show how emotionally invested the children became in this project:

Some reflections

As a first year teacher, this experience has taught me a great deal about teaching and learning through inquiry. What made it so fulfilling? I think the following elements played a crucial role:

Expectation – believing that children can achieve more than you think. As a new teacher, I find that coming fresh into teaching often brings about moments where I think… will this be too hard for them…I’ll just see how it goes and they always surprise me. Some children become experts and then they teach others. I was amazed at what they could do –as film makers, toy makers and activists!

Listening – letting the students have a voice/ drive the project at critical turning points. Often it was just a brief whole class discussion at the end of the day but the students always had questions and we responded to their questions – letting them guide the next stage of the inquiry.

Documentation We regularly displayed questions and student work so that students (and parents) could see the way the project was building over time and the children could see what their peers were thinking. Regular documentation helped us track and reflect on the inquiry.

Parent Involvement Our cohort was blessed with parents who had expertise in the areas we needed. But others were similarly keen to help. When things were overloaded, I organized a “Stitch and Socialise” night were I brought any sewing that the kids would find too tricky and the parents came to learn how to sew or just do their best to finish off the toys.

Teacher and community collaboration The teachers in my team all had different strengths which added to the engagement of the students. We relied heavily on experiences in the community and the emphasis was very much on primary sources. The students themselves – though young – collaborated throughout. Making the animated movies in small groups was the perfect vehicle for true collaboration – they had a shared goal and needed to do lots fo communicating and problem solving to make it happen. The use of ipads for this aspect of the inquiry was fantastic.

Authentic purpose. I have now seen how engaged kids are when they have a real purpose for their inquiry. At different stages in the inquiry…they recorded their invented games to share each other, they made films because they believed what they learned was worth sharing -and they also loved the idea of having a night time film festival where they would be the stars (wouldn’t you?). But perhaps the most powerful purpose was their drive to make a positive difference to the lives of other children. As the letters they wrote to accompany the toys attest – our children showed real empathy and compassion. This is an aspect of the inquiry I want to try to consider throughout my future as a teacher."

Hilary Green, July 2014

I am sure that readers of this blog will agree that this is an example of a rich, authentic inquiry. Let's keep reminding ourselves of the importance of real purposes and action for learning - asking kids "We KNOW this...but what can we DO about it?" - As Hilary's narrative shows, action itself can be the greatest catalyst for inquiry.

How well do your inquiries prompt powerful action?

Just wondering....

Planning for inquiry – an opportunity for growth and inspiration.

It’s mid-year planning season in many Australian schools. Each term, around this time, I find myself more often working with small teams of teachers around a planning table rather than in a classroom or at a podium. I admit, it’s one of my favourite things to do. I love the creative energy that inquiry planning demands of us. I love the challenge of connecting the children’s questions and interests with the resources we have, the curriculum and the teacher’s bigger picture view of where he/she wants to taker her students. I also love the fact that, in the schools I am fortunate enough to work in, teachers are prepared to have real conversations about the concepts the children will be exploring. We take time to ask ourselves what WE understand…over the last week I have had fascinating conversations about the nature of 'work', the true meaning of sustainability, what the term ‘states of matter’ REALLY means and why it's even worth learning about, the derivation of the word ‘commemorate’ , the relationship between force and energy, the complexities of the idea of a ‘balanced’ diet…I could go on! Looking back over the week, I am struck not only by the sheer diversity of ideas teachers grapple with as they plan but the increasing need for us to be strong inquirers ourselves. When we slow down our planning conversations and resist the urge to simply generate activities – we begin to ask questions and see our own confusions, uncertainties and gaps in our understandings. Here’s where the collaborative element of planning is so important. Taking time to toss ideas around, to challenge each other, to clarify to draw on our own experience not only enriches the conversation but provides a much more stable basis upon which to identify the key conceptual understandings for students. While I appreciate the intended message of the phrase ‘learning alongside the student’ in an inquiry classroom, I am also acutely aware of the way a teacher’s lack of clarity can lead to poor questioning and missed opportunities for deeper thinking. Taking time to talk through our own ways of seeing the ‘big picture’ of any inquiry journey is such a valuable component of the conversation around the planning table – and SO much richer than simply listing a bunch of achievement standards from a curriculum.

Collaborative planning for inquiry has become increasingly responsive and representative of the needs and interests of various groups and individuals. While teams still plan some similar strategies and experiences, the days of ‘cookie cutter’ units are over. When a team is clear about the bigger picture – there is greater flexibility in how different classes/students will travel towards it. One of my stand out moments for a really delightful week of planning was a conversation I had with the early years teachers at Roberts McCubbin Primary School here in Melbourne. Like many of the schools I work with, teachers at this level are encouraged to be on the look at for moments that lend themselves to authentic and powerful investigations. As we evaluated the inquiry work done over the term, one teacher in the team, Anita Siggins, had us all mesmerized by her sharing of the unexpected inquiry that unfolded when she brought in a perfectly sculpted, abandoned birds’ nest to show her children. This provocation opened up such rich learning for her fascinated students who have continued the most stunning investigation in their quest to find out what bird made it and how. As she shared her stories, photos, student questions, responses and documentation with us – her genuine delight in the experience was infectious and inspiring. I know we all went away from that meeting reminded of the power of a spontaneous, genuine inquiry.

I have said before on this blog, that I believe collaborative planning to be a valuable form of professional learning. In a worthwhile planning meeting we not only share but we inspire, challenge and question each other. And what results is far more than what goes ‘on the planner’ or ‘in the minutes’ – we grow ourselves as inquirers.

How inspiring are your planning meetings? Just wondering...

What teachers say about being inquirers.

Last week, I was fortunate to spend some time in a school with which I have had an ongoing partnership for a few years now. - Macquarie primary School in Canberra, Australia. As their work on developing approaches to inquiry in the classroom grows, there is a simultaneous interest in the ways in which inquiry can drive teacher learning. Schools as ‘communities of inquiry’ is not a new concept – but can be a challenging one to put into practice. This school has taken the bold step of appointing a teacher with expertise in higher degree research to act as a mentor teachers who are each engaged in an inquiry project of their choice. Like a growing number of schools, Macquarie is recognizing that in order for teachers to fully bring this ethos to their work with children – they need to see themselves as inquirers. Each teacher has selected an issue, problem or challenge to inquire into. The foci for their projects is, in most cases, is directly relevant to an identified area of need for their students as well as being something that they have a personal interest in as an educator. In many ways, these professional inquiries mirror the work we do with personalized inquiry for students such as ‘itime’ or ‘passion projects’ where we invite students to pursue questions of personal significance to them. During my meetings with teachers, I asked them to reflect on how deep involvement in an inquiry project was influencing their thinking about the way they work with inquiry in the classroom. Their reflections were honest and insightful. In this post, I am sharing some of these reflections- and the potential implications for how we engaging students in quality inquiry. I am so grateful to the great staff of Macquarie for allowing me to share in their journey and their permission to include their thoughts in this post.

| What teachers said about being inquirers | What that got us thinking about how we work with kids… |

| “It’s taking me longer than I thought it would. I need time.” | We need to provide kids with ample time for their inquiries. Let’s acknowledge that it DOES take more time to work this way and stop cluttering the path with too many 'activities'. |

| “I am passionate about this- so I am into it. I am so glad I didn't get told what I HAD to inquire into.” | Choice and voice are essential for motivation. Being given an opportunity to investigate things that are important to us is a powerful motivator – this kind of interest-based inquiry must be part of the landscape in our classrooms |

| “It’s been so frustrating because I can’t find much information on this. Only really academic articles that make my eyes glaze over…" | When kids can't access or understand the information they are gathering, motivation decreases and engagement is lost. We need to support students in finding relevant and accessible information. Frustration and confusion is inevitable, but if it goes on for too long it is counter-productive. |

| “At first felt like I lacked the skills to do this. I really needed our mentor to help me narrow my focus/use the right search tools and get me on track. Having those 1-1 conversations has been really helpful.” | The teacher’s role is essential. This role is a skills and process-based one. We need to offer our learners explicit instruction on HOW to inquire – and this ideally comes at the point of need. Teachers can’t always be across the content of all students’ inquiries – but they help provide the tools and processes, feedback and questions that help maintain momentum. Time for students to meet and discuss their inquiries is so important. |

| “I’ve changed my mind three times – but I am on track now. Once I started, I realized I was less interested in that than this! I basically had to start again but I know what I am doing now.” | We need to allow kids to change their minds! As we confer with students we should be asking – “how are you feeling about what you are doing?” We should consider giving them permission to change track if they can justify why. It’s what researchers do. |

| “Well…I feel like I’m not doing this properly. I am not really researching because I am basically just trying stuff out with my kids and reflecting on it.” | Kids often have a misconception about the term ‘research’ too! For many students, research is something you do when you ‘Google it’ or use a book. In fact, we can research by DOING, experimenting, observing, interviewing, viewing….we need to keep the concept of research broader and value a range of methodologies. |

| “It was suggested that I present this at a conference. It freaked me out! I thought, If I have to stand up at a conference and talk about this – I DON’T want to continue!” AndIt's so exciting because, I was told that I could share this at a conference which is a great opportunity!” | Do we stifle enthusiasm for investigation when we insist on public sharing of learning? For some children, I have no doubt that we do. Conversely, others will be highly motivated by the opportunity to bring their learning to a wider audience. Again – choice and diversity are the keys. |

| “I have made a start but I don’t think I really know what my question is yet.” | It has been common practice to ask students to begin to design an inquiry by framing a question. Some inquiries, however, require exploration before we can figure out what it is we need to ask. Do we model this to students? Even when we use an inquiry cycle … we need to show students that starting points will vary according to context and prior learning. |

| “It feels a bit all over the place. I am doing bits and pieces but I think that’s OK –I think it will come together. I'm finding out some fascinating things.” | Inquiry is often messy. We need to acknowledge this as we engage in both guided and more open inquiry with students. While the process should be made explicit, we must show should the recursive nature of that process. Presenting the journey as a strictly linear one (e.g. “the scientific process’) can be misleading and unhelpful. |

| “I am working on something I am very passionate about – but it actually makes me feel quite vulnerable. What if people don’t care about it like I do? What if others think I’ve chosen something silly? What if I find I am questioned or challenged about it? How will I cope with that?”

We can learn so much about inquiry by being inquirers ourselves. How often do we stop to reflect on our own experience of this process - both formal and informal? And what connections do we make between our learning and our students' learning...? Just wondering....

|

This beautifully honest comment made us all think about the flip side of allowing students to pursue their passions in the very public and collaborative context of a classroom. We need to remember that our passions often form part of our identity…they matter to us. Some students may choose to investigate things we deem less important or less worthy than others – but they matter to THEM. Permission to explore passions needs to be given alongside a commitment to respect and support the individual’s interests. Questioning needs to happen from a disposition of genuine curiosity rather than skepticism or judgment.

|