“Rivers have life and sound and movement and infinity of variation, rivers are veins of the earth through which the lifeblood returns to the heart.” - Roderick Haig-Brown

I am days away from re-entering the fray. Back to airports, hotel rooms, workshop venues and, my favourite (less ‘fray’, and more fabulous) schools. Like several other countries in the Southern Hemisphere, Australian schools are soon to begin a new year. Inevitably this time brings with it a strong sense of intention and the urge to improve, refresh or re-make ourselves in some way. As another year of teaching and learning invites me in, I recognise the same yearning: to be heart-led. It is easy (and perhaps easier as I get older) to become cynical, frustrated and jaded over time but curiosity is the greatest antidote to cynicism or complacency. Curiosity is the ‘life blood’ of my work as an educator. It reminds me why I do what I do.

Over a decade ago, I wrote a post exploring the idea of choosing a word for the year. As an alternative to ‘resolutions,’ nominating a single word has gained mainstream popularity and can be a useful exercise for teachers and students alike. I revisited that concept two years later, this time suggesting some of the words that might power up an inquiry stance. In 2015, I pondered some questions that could assist educators in building a culture of inquiry from day 1. Ten years later, at the beginning of 2025, I shared some of the questions I have found useful to keep my thinking ‘tight yet loose.’

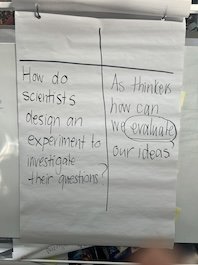

As I write my first post for 2026, I am again leaning into the essence of inquiry: curiosity and questioning. I know I need to stay relentlessly curious and notice the beautiful questions that both energise and sustain me personally. Like rivers, some of these questions are permanent and propel my thinking each day -and others appear as a result of new conditions - personally and globally. Perhaps some of these questions will echo your own curiosities? Perhaps the “I” could become a ‘we’ as a shared question for a team. Perhaps my own questions might prompt a similar exercise for you. As the year begins, I am curious about …

children … What “image of the child” do I hold at this time in my career? When I think about the children who will walk through the door in each classroom I work in, what comes to mind? How will I choose to ‘see’ them even before I meet them?

my role … What image of myself as an educator do I hold at this time in my career? What metaphors resonate with me? Am I a gardener? An artist? A conductor? What metaphors am I most drawn to? How might my metaphors be limiting me?

growth … What might I try to let go of this year in order to be more of the educator I want to be? What no longer serves me (and my learners) well? What would I abandon tomorrow if no one was watching or judging? What habits or patterns do I want to break or make?

courage … How might I be ‘half a shade braver’ this year? How might I challenge myself to take a risk, try something new or stretch myself as a learner and as a teacher? What would I do if I knew I couldn’t fail? How can I effectively stand by my principles while remaining open to new insights and perspectives?

environments … If my classroom/staffroom/workshop space was a habitat, what kind of life would it sustain? How might both the indoor and outdoor spaces nurture the kind of learning I value? How might the spaces I curate better nurture thinking, wonder and collaboration?

time … How might I improve my relationship with time? What might it mean to be less of a slave to the clock? What if I chose to be grateful for the time I have rather than frustrated by the lack of it?

play … What might a more playful approach look like for me this year? How can I amplify the role of play as I work with educators and children?

joy … What brings me joy in my teaching and what can I do to connect with that source of joy more regularly? How can I end my days energised rather than depleted? How might I help myself notice and honour joy?

learning … What do I want to learn more about this year? How might I experience something as a beginner? How will I widen and deepen my understanding of that which I am most curious? How can I release myself from the shackles of shallow social media posts and engage in deep, sustained reading more often?

connection … What can I do to stay human in this work? How might I stay connected – to my passion and purpose and to the colleagues, children and families in my teaching and learning communities?

nuance … In an era less tolerant of difference and driven by a need for certainty, how might I stay comfortable with uncertainty and even more willing to consider alternative perspectives? How can I help myself hold questions rather than needing answers?

These questions feel like gentle rivers flowing into the ocean of the year – or perhaps the ocean of my expanding experience as an educator. They are designed to keep me reflective, mindful and curious. But they are my questions. I wonder what yours might be?